Despite their demonstrated military effectiveness, many colonial Americans harbored a deep suspicion toward European-style standing armies. Colonists’ experiences with the British redcoats in the decade leading up to the War of Independence were usually negative, suggesting that professional soldiers were coarse and unthinking. The disaster at what the colonists came to call the Boston Massacre underlined these impressions.

Despite their demonstrated military effectiveness, many colonial Americans harbored a deep suspicion toward European-style standing armies. Colonists’ experiences with the British redcoats in the decade leading up to the War of Independence were usually negative, suggesting that professional soldiers were coarse and unthinking. The disaster at what the colonists came to call the Boston Massacre underlined these impressions.

Many American colonists worried that the demands of a disciplined, professional army stood fundamentally at odds with cherished values: the American belief in republican individualism, for example, did not appear consistent with the professional soldier’s unquestioning duty to his commander. And Americans resented the extreme expense involved with raising and maintaining a permanent army. Many of the hated taxes levied on them in the 1760s and 1770s went to defray the expenses of maintaining the British military presence in North America.

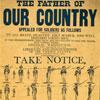

Even as the Continental Army was securing the victories that made American independence possible, worries arose about what to do with the institution after the peace. The recruiting poster pictured here – from World War I – draws on a poster first issued to recruit soldiers during the Revolutionary War. It was not until after World War II that the United States established a large standing army during peacetime.

Source:

“The father of our country appealed for soldiers as follows: to all brave, healthy, able bodied, and well disposed young men [...],” from the World War I Posters collection at the Library of Congress, (accessed September 12, 2012).